Key Takeaways

- Canine glaucoma is characterized by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) that damages the retina and optic nerve, potentially causing permanent blindness

- Primary glaucoma is inherited and affects specific breeds like Basset Hounds, Boston Terriers, and Beagles, while secondary glaucoma results from other eye diseases or injuries

- Early recognition of symptoms including sudden eye pain, redness, corneal cloudiness, and vision loss is critical for emergency treatment

- Treatment requires immediate IOP reduction through medications, surgery, or both, with lifelong management necessary for primary glaucoma

- Regular veterinary eye exams and tonometry are essential for early detection, especially in predisposed breeds

Canine glaucoma is characterized by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) that damages the retina and optic nerve, potentially causing permanent blindness

Primary glaucoma is inherited and affects specific breeds like Basset Hounds, Boston Terriers, and Beagles, while secondary glaucoma results from other eye diseases or injuries

Early recognition of symptoms including sudden eye pain, redness, corneal cloudiness, and vision loss is critical for emergency treatment

Treatment requires immediate IOP reduction through medications, surgery, or both, with lifelong management necessary for primary glaucoma

Regular veterinary eye exams and tonometry are essential for early detection, especially in predisposed breeds

Understanding Canine Glaucoma

Canine glaucoma represents one of the most serious threats to your dog’s vision, characterized by dangerously elevated intraocular pressure that can cause irreversible blindness within hours. Unlike humans, where glaucoma often develops slowly, dogs glaucoma frequently presents as a medical emergency—owners should seek help from a veterinarian immediately to prevent irreversible damage.

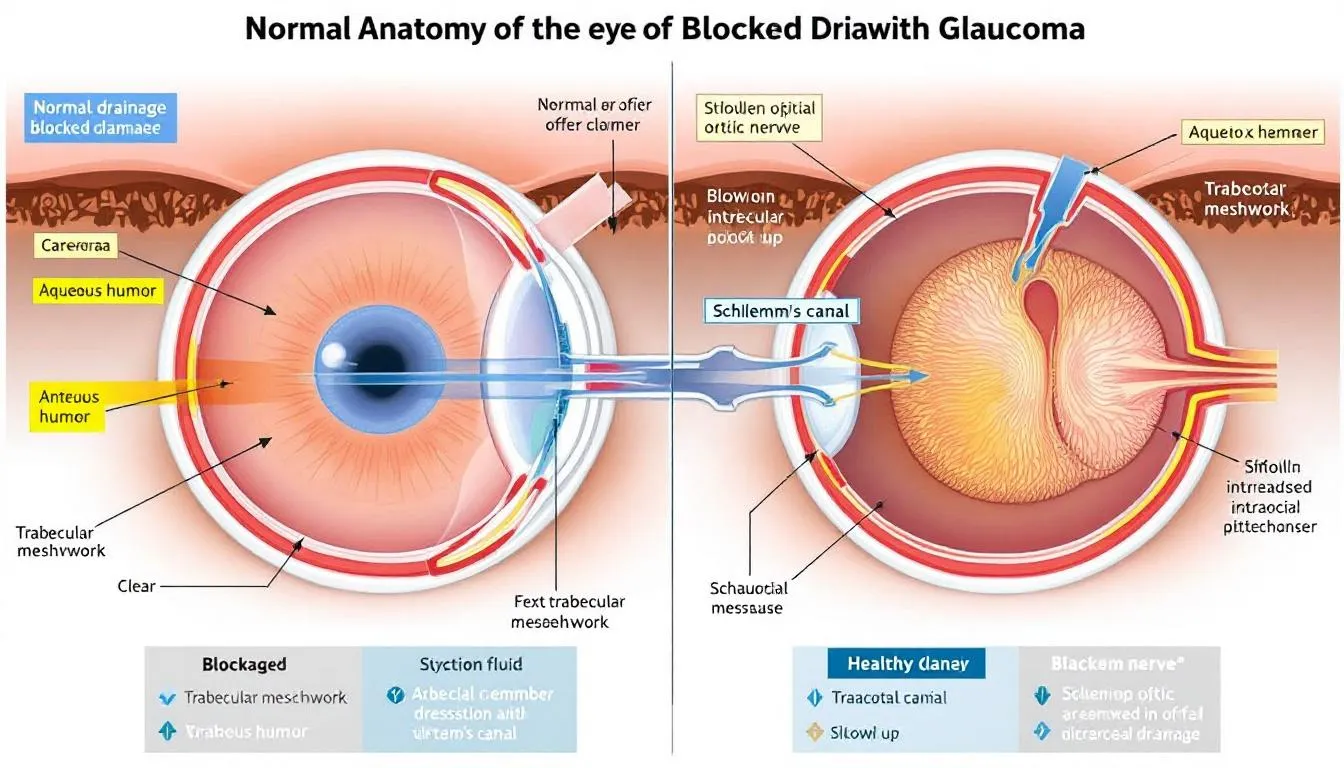

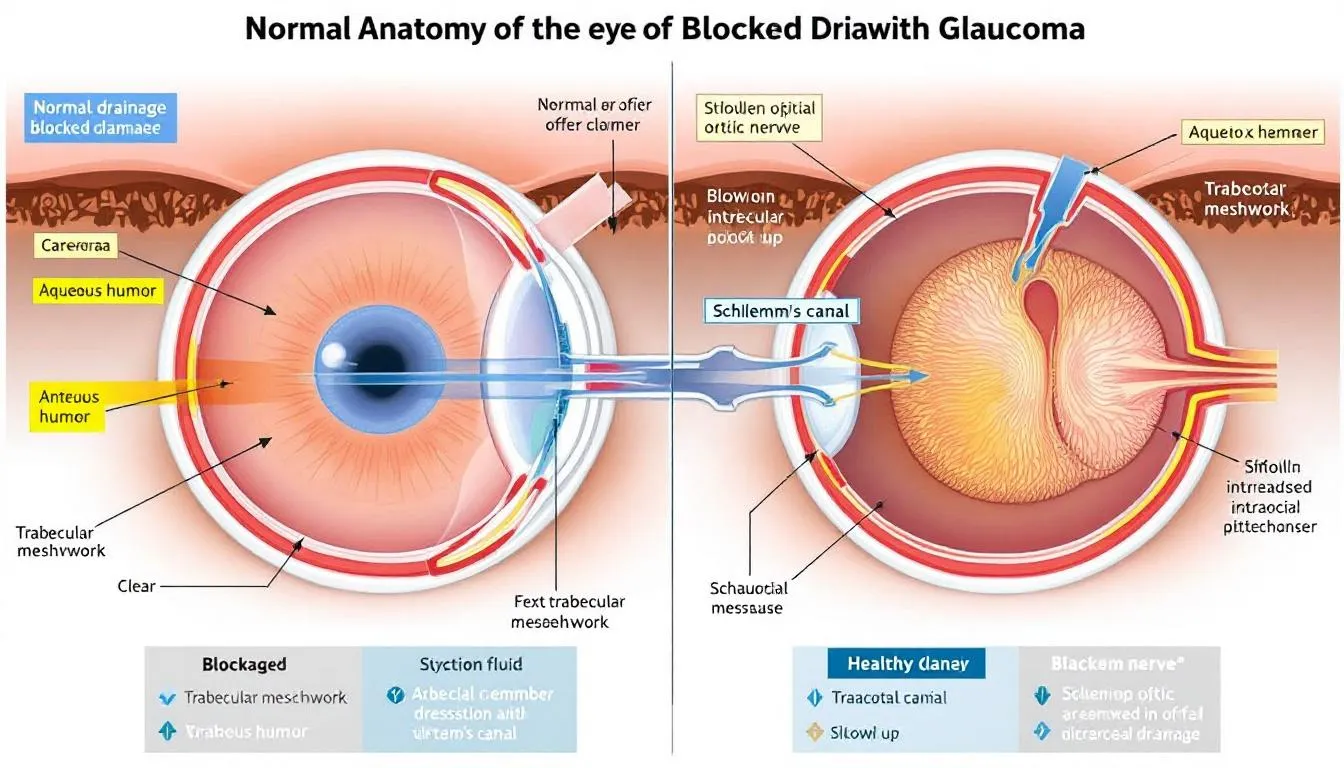

The condition occurs when the delicate balance of fluid production and drainage within the eye becomes disrupted. The ciliary body continuously produces aqueous humor, a clear fluid that nourishes the eye’s internal structures and maintains proper eye pressure. This fluid normally drains through the iridocorneal angle, a microscopic drainage system located where the iris meets the cornea.

When this drainage of aqueous humor becomes blocked or inadequate, pressure builds rapidly inside the eye. Inadequate drainage of aqueous humor is a primary cause of glaucoma, leading to increased intraocular pressure. Outflow obstruction in the aqueous humor drainage pathways, such as the uveal and corneoscleral meshworks, can result in impaired fluid outflow and contribute to the development and progression of glaucoma. Normal iop in dogs ranges from 15-25 mm Hg, but glaucoma occurs when pressures exceed this range, often reaching dangerous levels above 40-60 mm Hg during acute episodes.

The increased pressure compresses delicate tissues, particularly the retina and optic nerve, cutting off blood flow and causing irreversible damage to retinal ganglion cells. These specialized nerve cells transmit visual information from the eye to the brain, and once destroyed, they cannot regenerate.

The distinction between acute glaucoma and chronic glaucoma is crucial for treatment success. Acute stages involve sudden pressure spikes that constitute true emergencies, while chronic forms develop gradually over time, often going unnoticed until significant vision loss has occurred.

Anatomy of the Canine Eye

The canine eye is a marvel of biological engineering, composed of intricate structures that work together to capture and process visual information. At the front of the eye lies the cornea, a transparent dome that not only protects the eye but also helps focus incoming light. Just behind the cornea is the anterior chamber, filled with aqueous humor—a clear fluid essential for maintaining normal intraocular pressure and nourishing internal eye tissues.

The iris, the colored part of the eye, acts like a camera shutter, adjusting the size of the pupil to control how much light enters. Directly behind the iris sits the lens, a flexible, transparent structure that fine-tunes focus, ensuring that light rays converge precisely on the retina at the back of the eye.

The retina is a delicate, light-sensitive layer lining the inner surface of the eye. It contains specialized photoreceptor cells that convert light into electrical signals. These signals are then transmitted via the optic nerve—a thick bundle of nerve fibers—directly to the brain, where they are interpreted as images. The health of the optic nerve is critical, as damage here can result in irreversible vision loss, a hallmark of glaucoma in dogs.

Unique to canine patients is the tapetum lucidum, a reflective layer behind the retina that enhances night vision by reflecting light back through the retina, giving dogs their characteristic eye shine in the dark.

Understanding the anatomy of the canine eye, especially the pathways for aqueous humor drainage and the vulnerability of the optic nerve, is fundamental in veterinary ophthalmology. It provides the foundation for diagnosing and managing conditions like primary and secondary glaucoma, where disruptions in fluid flow or increased intraocular pressure can threaten the delicate balance required for healthy vision.

Types of Canine Glaucoma

Understanding whether your dog has primary or secondary glaucoma fundamentally shapes treatment approach and prognosis. Primary angle closure glaucoma, also known as closed angle glaucoma, is characterized by developmental abnormalities that lead to angle closure and increased intraocular pressure. This form often presents acutely with pain and vision loss, and certain breeds, such as Cocker Spaniels and Basset Hounds, are predisposed. This distinction helps veterinary ophthalmologists determine the most effective intervention strategy and provides realistic expectations for outcomes.

Primary Glaucoma

Primary glaucoma develops due to inherited genetic abnormalities affecting the eye’s drainage system. This progressive disease typically affects both eyes, though symptoms often appear in one eye first. Primary glaucoma develops most commonly in middle-aged to older dogs from predisposed breeds.

Primary open angle glaucoma represents the rarer form, primarily affecting Beagles and Norwegian Elkhounds with specific mutations in the ADAMTS10 gene. In these cases, the drainage angle remains physically open, but microscopic changes in the trabecular meshwork reduce outflow efficiency. The disease progresses slowly over months to years, making early detection through regular screening particularly important.

Primary angle closure glaucoma occurs much more frequently and involves structural abnormalities of the irido corneal angle. Many affected dogs have pectinate ligament dysplasia, a developmental abnormality that predisposes them to angle closure. The condition typically follows a reverse pupillary block mechanism, where aqueous humor becomes trapped in the posterior chamber, pushing the peripheral iris forward and blocking drainage through the iridocorneal angle.

Secondary Glaucoma

Secondary glaucoma results from other eye diseases or trauma that disrupts normal aqueous humor drainage. Unlike primary forms, secondary glaucoma may affect only one eye initially and sometimes can be prevented or cured by addressing the underlying cause.

Lens luxation represents one of the most common causes, particularly in terrier breeds. When the lens dislocates into the anterior chamber, it can block the pupil or physically obstruct the drainage angle, causing rapid iop elevation. This situation requires emergency treatment, as the presence of an anteriorly luxated lens makes many glaucoma medications dangerous to use.

Other conditions leading to secondary glaucoma include chronic uveitis (inflammation inside the eye), intraocular tumors, advanced cataracts, and trauma. Each underlying cause requires specific treatment approaches, making accurate diagnosis essential for successful management.

Breed Predisposition and Risk Factors

Certain breeds face dramatically higher risks for developing glaucoma due to inherited anatomical features affecting the drainage angle. Understanding these predispositions helps owners and veterinarians implement appropriate screening and preventive measures.

High-risk breeds include Akita, Basset Hound, Boston Terrier, Chow Chow, Cocker Spaniel, and Dalmatian. Additional breeds with elevated risk encompass Beagle, Bull Mastiff, Miniature Schnauzer, Poodle, Samoyed, and Shar Pei. Within these breeds, females often face higher risk due to anatomically smaller angle opening distances.

The inheritance pattern for most primary glaucomas appears complex, involving multiple genes rather than simple dominant or recessive traits. This complexity makes breeding decisions challenging, as even dogs with normal gonioscopy results may carry genes that predispose their offspring to glaucoma.

Age-related factors also influence glaucoma development. As dogs age, their lenses naturally thicken and the ciliary body may undergo changes that narrow the drainage angle. In predisposed breeds, these normal aging changes can trigger acute glaucoma attacks in dogs that previously showed no symptoms.

Environmental and physiological factors may also play roles. Stress, excitement, or any condition causing pupil dilation can potentially precipitate attacks in susceptible animals. Some dogs experience seasonal patterns, with attacks more common during periods of changing daylight hours.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Recognizing the clinical signs of glaucoma can mean the difference between preserving your dog’s vision and permanent blindness. The presentation varies dramatically between acute and chronic forms, with acute cases requiring immediate veterinary attention.

Acute Glaucoma Signs

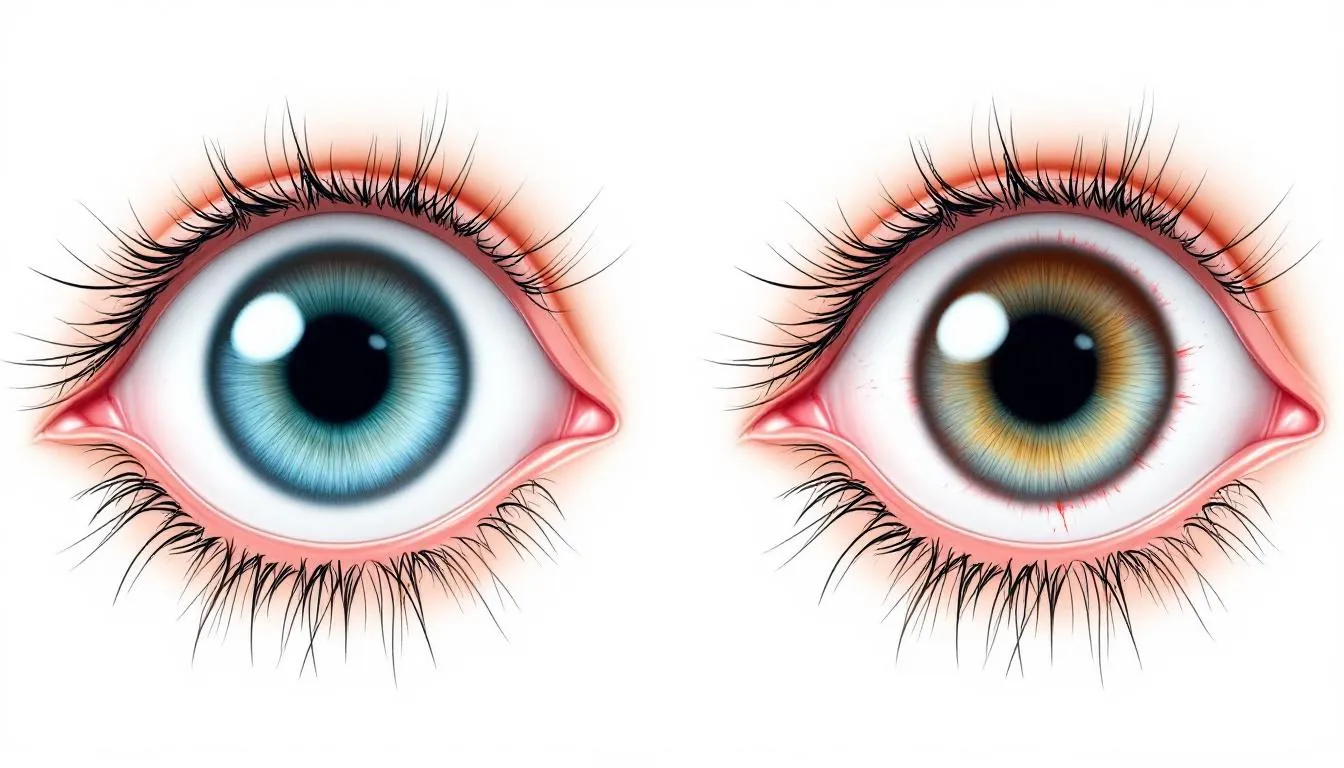

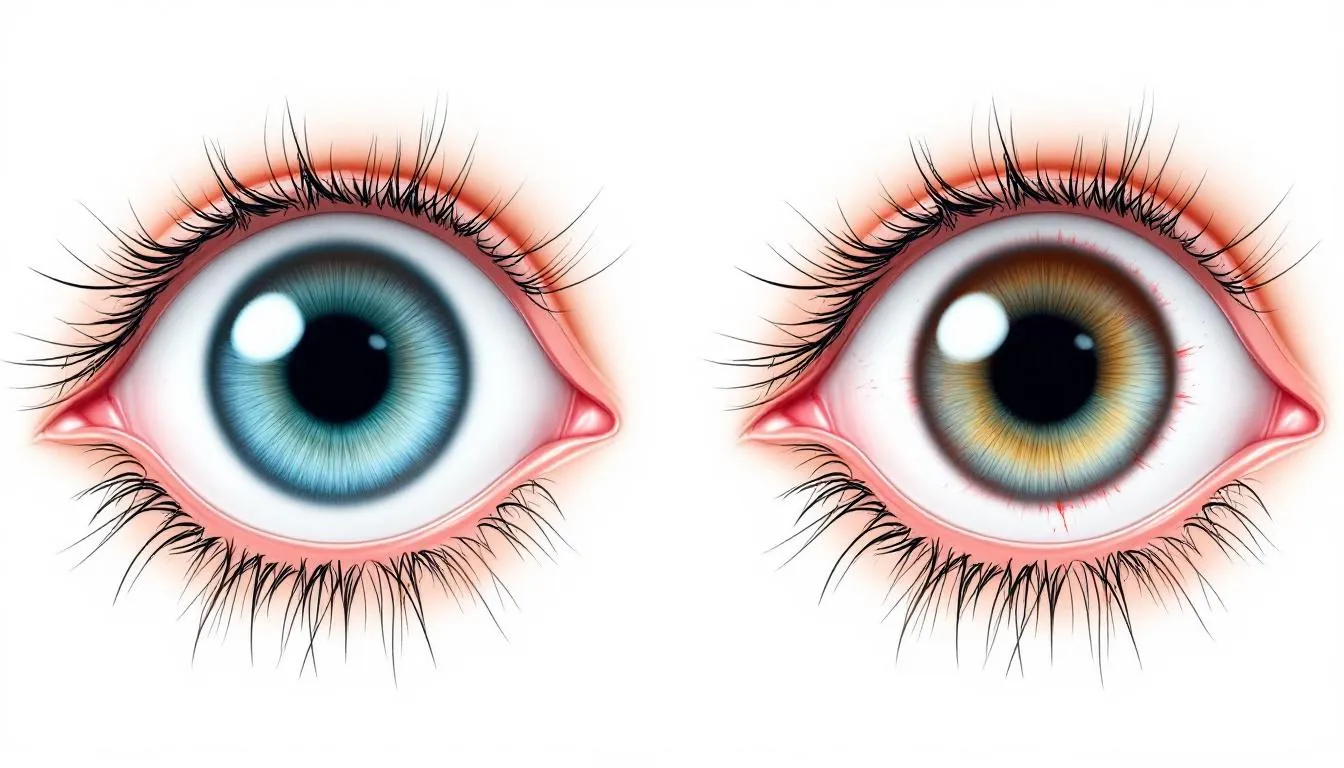

Acute glaucoma produces unmistakable signs of severe pain and rapid vision loss. Dogs typically develop sudden, intense blepharospasm (squinting) and may paw at the affected eye or rub their face against furniture. The eye becomes visibly red due to episcleral injection, giving it a bloodshot appearance that’s particularly noticeable in the white part of the eye.

Corneal edema develops rapidly, causing the normally clear cornea to appear blue, cloudy, or hazy. This diffuse corneal edema results from elevated eye pressures affecting the corneal endothelium’s ability to maintain corneal clarity. The pupil typically becomes dilated and fixed, failing to respond normally to light.

Vision loss can occur within 12-24 hours of pressure elevation, making immediate veterinary care essential. Many dogs also develop systemic signs including nausea, vomiting, lethargy, and decreased appetite due to severe pain. The affected eye may feel noticeably harder than the normal eye when gently palpated.

Chronic Glaucoma Signs

Chronic glaucoma presents with more subtle but equally serious changes that indicate sustained pressure elevation over time. The most obvious sign is buphthalmos, or enlargement of the eyeball, which typically indicates that significant vision loss has already occurred.

Dogs with chronic glaucoma may develop Haab striae, which appear as linear breaks or streaks in the corneal surface caused by stretching from increased pressure. The lens may become subluxated or completely luxated due to changes in the eye’s internal structure.

Examination of the optic disc reveals cupping and pallor, signs of optic nerve damage that correlate with vision loss. Unlike acute cases, chronic glaucoma may produce less obvious episcleral injection, making the condition easier to overlook.

End stage glaucoma can progress to phthisis bulbi, where the eye becomes shrunken and non-functional. While this eliminates the pain associated with elevated pressure, it represents complete and irreversible vision loss.

Diagnosis of Canine Glaucoma

Accurate diagnosis of glaucoma requires specialized equipment and expertise, emphasizing the importance of prompt veterinary evaluation when symptoms appear. It is crucial to accurately measure IOP for diagnosis, as current tonometry methods estimate rather than directly measure IOP. The diagnostic process involves multiple techniques to confirm elevated pressure, identify the underlying cause, and assess the extent of damage. Eyes that have undergone intraocular surgery may yield less accurate IOP measurements due to changes in ocular rigidity.

Tonometry (IOP Measurement)

Tonometry provides the definitive measurement of intraocular pressure and represents the most critical diagnostic test for glaucoma. Two main types of tonometers are commonly used in veterinary medicine, each with specific advantages and techniques.

Applanation tonometry, using devices like the Tono-Pen, measures the force required to flatten a specific area of the corneal surface. This technique requires topical anesthetic drops and careful technique to ensure accurate readings. The device must be properly calibrated and held perpendicular to the cornea for reliable results.

Rebound tonometry, exemplified by the TonoVet, measures how quickly a small probe bounces off the corneal surface. This method offers the advantage of not requiring topical anesthetic and includes species-specific algorithms for canine patients. The technique is generally easier to perform and less stressful for dogs.

An iop difference greater than 10 mm Hg between eyes strongly suggests glaucoma, even if both measurements fall within the normal range. Serial measurements over time provide more reliable information than single readings, as normal eye pressures can fluctuate throughout the day.

Gonioscopy and Advanced Imaging

Gonioscopy involves using a special goniolens to examine the iridocorneal angle structure directly. This technique helps differentiate primary from secondary glaucoma and identifies anatomical abnormalities that predispose to angle closure. The procedure requires topical anesthesia and specialized training to interpret results accurately.

High-frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) provides detailed images of the anterior chamber and ciliary cleft, revealing subtle changes in iris configuration and angle structure. This non-invasive technique can detect early signs of angle narrowing before clinical symptoms appear.

Anterior-segment optical coherence tomography offers another non-invasive imaging option for evaluating angle anatomy and measuring anterior chamber depth. These advanced imaging techniques are particularly valuable for screening breeding animals and monitoring disease progression.

Additional Diagnostic Tests

A complete ophthalmic examination includes thorough evaluation of all eye structures, with particular attention to the optic disc and retinal blood vessels. Fundoscopy can reveal changes associated with glaucoma, including optic disc cupping, pallor, and retinal degeneration.

Vision testing through obstacle courses and response to visual stimuli helps assess functional vision status. This information guides treatment decisions and provides owners with realistic expectations about their dog’s capabilities.

Red-free photography can detect early retinal nerve fiber layer defects that may not be visible with standard examination techniques. Electroretinography (ERG) measures retinal function and can help distinguish between glaucoma and other causes of vision loss in complex cases.

Emergency Treatment of Acute Glaucoma

When acute glaucoma is diagnosed, every minute counts in preserving vision. The goal is to reduce elevated iop as quickly as possible while minimizing potential complications from rapid pressure changes.

Immediate IOP Reduction

Osmotic diuretics, particularly mannitol administered intravenously at 1-2 g/kg over 30 minutes, provide the fastest method for reducing intraocular pressure. This treatment works by drawing excess fluid from the eye into the bloodstream, but requires careful monitoring for cardiovascular disease or kidney dysfunction.

Water restriction for 3-4 hours during osmotic diuretic treatment prevents dilution of the osmotic effect and maximizes pressure reduction. Some cases may require anterior chamber paracentesis, a procedure where a small needle removes aqueous humor directly from the anterior chamber for immediate pressure relief.

The target is to reduce iop within the first few hours of treatment, ideally bringing pressures below 25 mm Hg to halt ongoing optic nerve damage. However, pressure reduction must be gradual enough to avoid complications from sudden changes in eye pressure.

Topical Medications

Multiple classes of topical medications work through different mechanisms to control intraocular pressure. Prostaglandin analogues like latanoprost and travoprost increase unconventional outflow pathways and can dramatically reduce pressure, but are contraindicated when uveitis or lens luxation is present.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as dorzolamide and brinzolamide reduce aqueous humor production by the ciliary body. These medications form the backbone of long-term glaucoma management and can be used safely in most cases.

Topical miotics like pilocarpine work by constricting the pupil and mechanically opening the iridocorneal angle. While effective in some cases, these medications can worsen angle closure in others, requiring careful case selection.

When using topical anti-inflammatory therapies, it is important to maintain a healthy ocular surface, as this can improve drug efficacy and help manage inflammation more effectively.

Combination therapy using multiple medication classes often provides better pressure control than single agents alone. The key is selecting compatible medications that work through different mechanisms without causing adverse interactions.

Long-term Management and Maintenance Therapy

Successful long-term management of glaucoma requires consistent medication administration, regular monitoring, and owner commitment to lifelong treatment. The goal shifts from emergency pressure reduction to maintaining stable, low pressures that preserve remaining vision and prevent pain.

Medication Protocols

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors typically serve as first-line therapy for sustained iop control due to their safety profile and effectiveness. Both topical and oral formulations are available, with topical versions preferred to minimize systemic side effects.

Beta-blockers like timolol and betaxolol can provide additional pressure reduction but require caution in dogs with cardiovascular disease or respiratory conditions. These medications reduce aqueous humor production and can be combined safely with most other glaucoma medications.

Prostaglandin analogues remain highly effective for pressure control but are contraindicated in cases involving uveitis or lens luxation. When appropriate, these medications can provide excellent long-term control with once-daily dosing.

Proper eye drop administration technique is crucial for medication effectiveness. Owners should instill one drop, hold the eye open for 30-60 seconds, and wait several minutes between different medications. Many dogs benefit from positive reinforcement training to make medication administration easier.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Initial iop monitoring may require measurements every 8-12 hours to ensure adequate pressure control, gradually extending to every 2-5 days as stability is achieved. Long-term monitoring typically involves monthly to quarterly veterinary visits depending on disease stability.

Regular tonometry using the same device and technique ensures consistent measurements over time. Owners should maintain detailed records of medication administration and any changes in their dog’s behavior or eye appearance.

Medication efficacy may decrease over time, requiring combination therapy or medication changes. Some dogs develop tolerance to specific medications, necessitating periodic adjustments to maintain adequate pressure control.

Prophylactic treatment of the unaffected eye becomes essential in primary glaucoma cases, as the disease is bilateral by nature. Early intervention in the second eye can delay onset and preserve vision significantly longer than waiting for symptoms to appear.

Surgical Treatment Options

When medical management fails to control intraocular pressure adequately, surgical intervention becomes necessary to preserve vision or provide pain relief. Surgical options range from drainage procedures to destructive surgeries depending on the eye’s visual potential.

Drainage Procedures

Drainage tube implants create alternative pathways for aqueous humor outflow when the natural drainage system fails. These devices, typically made of silicone or other biocompatible materials, redirect fluid from inside the eye to a reservoir or absorption area beneath the conjunctiva.

Laser cyclophotocoagulation targets the ciliary body to reduce aqueous humor production. This procedure uses laser energy to selectively destroy portions of the ciliary body while preserving surrounding tissues. Multiple treatment sessions may be necessary to achieve adequate pressure reduction.

Cryotherapy provides another option for partial ciliary body destruction, using freezing temperatures to reduce aqueous production. While effective, this procedure carries higher risks of complications compared to laser treatments.

Success rates for drainage procedures vary widely depending on the underlying cause of glaucoma and the eye’s overall condition. These surgeries often require combination with continued medical therapy for optimal results.

Salvage Procedures

Enucleation, or surgical removal of the eye, provides definitive pain relief for blind, painful eyes that don’t respond to medical or other surgical treatments. While emotionally difficult for owners, this procedure often dramatically improves quality of life for dogs suffering from chronic ocular pain.

Evisceration with prosthesis placement offers a cosmetic alternative to enucleation in select cases. This procedure removes the eye’s contents while preserving the outer shell, allowing placement of an artificial eye for appearance.

Intrascleral prosthesis placement represents another cosmetic option where the eye’s contents are replaced with a silicone sphere. This procedure maintains the eye’s general shape and movement while eliminating pain.

The primary goals of salvage procedures are pain relief and improved quality of life rather than vision preservation. Many owners report their dogs become more active and social after successful pain management through these procedures.

Complications of Glaucoma

Glaucoma is not only a threat to vision but can also lead to a cascade of serious complications if not addressed promptly. As intraocular pressure rises, the delicate retina and optic nerve are subjected to increasing stress, resulting in progressive and often irreversible vision loss. This damage can manifest as blind spots, reduced peripheral vision, or complete blindness as the disease progresses.

One of the earliest and most distressing complications is severe pain, caused by the stretching of sensitive eye tissues and the buildup of pressure within the globe. Dogs may show signs of discomfort such as squinting, pawing at the eye, or behavioral changes. Corneal edema, or swelling of the cornea, often develops as increased intraocular pressure impairs the function of the corneal endothelium, leading to a cloudy, bluish appearance and further discomfort.

Secondary glaucoma can arise as a complication of other eye conditions, such as lens luxation, where the lens shifts out of place and blocks normal fluid drainage, or from intraocular tumors and chronic inflammation (uveitis). These underlying issues can further elevate intraocular pressure and accelerate damage to the retina and optic nerve.

If glaucoma remains uncontrolled, the eye may progress to end stage glaucoma. At this point, the eye is not only blind but also persistently painful, often becoming enlarged (buphthalmos) or shrunken (phthisis bulbi). In such cases, enucleation—the surgical removal of the eye—may be the only option to relieve suffering and restore quality of life.

Ultimately, the complications of glaucoma underscore the importance of early detection, aggressive management, and regular monitoring to prevent the devastating consequences of increased intraocular pressure on the retina and optic nerve.

Prognosis and Prevention

The prognosis for canine glaucoma depends heavily on early detection and prompt treatment initiation. Understanding realistic expectations helps owners make informed decisions about their dog’s care while emphasizing the importance of preventive measures.

Visual Prognosis

Early diagnosis and treatment within 12-24 hours of symptom onset provides the best chance for vision preservation. However, even with optimal treatment, many dogs experience some degree of permanent vision loss due to the irreversible nature of retinal ganglion cell damage.

Primary glaucoma generally carries a guarded prognosis requiring lifelong management and frequent monitoring. The bilateral nature of the disease means that even successfully treated eyes remain at risk for future pressure elevations.

Secondary glaucoma may offer better outcomes if the underlying cause can be identified and treated effectively. For example, prompt surgical removal of a luxated lens may restore normal drainage and prevent further pressure elevation.

Chronic changes including buphthalmos indicate poor visual prognosis, as these structural changes suggest prolonged pressure elevation and extensive damage. However, many dogs adapt remarkably well to vision loss and maintain good quality of life with appropriate support.

Prevention Strategies

Regular veterinary eye exams for high-risk breeds starting at 3-4 years of age enable early detection before symptoms appear. Annual tonometry screening can identify pressure elevations in their earliest stages when treatment is most effective.

Gonioscopy evaluation in breeding dogs helps identify pectinate ligament dysplasia and other anatomical abnormalities that predispose to glaucoma. This information supports informed breeding decisions to reduce disease inheritance in affected breeds.

Genetic counseling and selective breeding practices can help reduce the incidence of inherited glaucoma over time. As researchers identify specific genetic markers associated with glaucoma, genetic testing may become available to guide breeding decisions.

Prophylactic therapy for high-risk dogs or those with early anatomical changes may help delay disease onset. Close collaboration with a veterinary ophthalmologist helps determine when preventive treatment is appropriate for individual dogs.

FAQ

Can my dog live a normal life with glaucoma?

Dogs can adapt remarkably well to vision loss and maintain good quality of life with proper management. Early treatment and consistent medication help preserve remaining vision when possible. Pain control is essential - many dogs show improved behavior and activity levels after effective treatment. Environmental modifications like avoiding rearranging furniture and using verbal cues help blind dogs navigate safely. Most dogs with well-managed glaucoma continue to enjoy walks, play, and normal interactions with their families.

How quickly does glaucoma progress in dogs?

Acute glaucoma can cause permanent blindness within 12-24 hours without immediate treatment, making it a true veterinary emergency. Primary open angle glaucoma progresses slowly over months to years, allowing more time for intervention. Primary angle closure glaucoma often has intermittent episodes before sustained elevation, which may provide warning signs for attentive owners. Individual progression varies significantly based on the underlying cause, breed predisposition, and response to treatment.

Should I treat the unaffected eye in my dog with unilateral glaucoma?

Yes, prophylactic treatment is strongly recommended for the unaffected eye in primary glaucoma cases. Primary glaucoma is bilateral by nature - the second eye will eventually be affected in most cases. Betaxolol eye drops can significantly delay onset of glaucoma in the contralateral eye when started early. Gonioscopy helps confirm primary glaucoma and guide prophylactic therapy decisions. Early intervention in the second eye often preserves vision much longer than waiting for symptoms to appear.

What is the difference between normal eye pressure fluctuations and glaucoma?

Normal iop in dogs ranges from 15-25 mm Hg with slight daily variations that are usually less than 5 mm Hg. Glaucoma typically involves sustained pressures above 25 mm Hg or significant pressure differences between eyes greater than 10 mm Hg. Single elevated readings should always be confirmed with repeat measurements, as stress or improper technique can cause temporary elevations. Clinical signs such as pain, redness, corneal cloudiness, and vision changes help differentiate true glaucoma from normal fluctuations.

Are there any new treatments for canine glaucoma on the horizon?

Research continues to focus on neuroprotective agents that could preserve retinal ganglion cells even in the presence of elevated pressure. Gene therapy trials are investigating treatments for inherited forms of glaucoma, particularly in breeds with identified genetic mutations. Novel drug delivery systems including sustained-release implants are being developed to improve medication compliance and effectiveness. Stem cell therapy and retinal regeneration remain experimental but promising areas that may offer hope for restoring vision in the future.

FAQ

Can my dog live a normal life with glaucoma?

Dogs can adapt remarkably well to vision loss and maintain good quality of life with proper management. Early treatment and consistent medication help preserve remaining vision when possible. Pain control is essential - many dogs show improved behavior and activity levels after effective treatment. Environmental modifications like avoiding rearranging furniture and using verbal cues help blind dogs navigate safely. Most dogs with well-managed glaucoma continue to enjoy walks, play, and normal interactions with their families.

How quickly does glaucoma progress in dogs?

Acute glaucoma can cause permanent blindness within 12-24 hours without immediate treatment, making it a true veterinary emergency. Primary open angle glaucoma progresses slowly over months to years, allowing more time for intervention. Primary angle closure glaucoma often has intermittent episodes before sustained elevation, which may provide warning signs for attentive owners. Individual progression varies significantly based on the underlying cause, breed predisposition, and response to treatment.

Should I treat the unaffected eye in my dog with unilateral glaucoma?

Yes, prophylactic treatment is strongly recommended for the unaffected eye in primary glaucoma cases. Primary glaucoma is bilateral by nature - the second eye will eventually be affected in most cases. Betaxolol eye drops can significantly delay onset of glaucoma in the contralateral eye when started early. Gonioscopy helps confirm primary glaucoma and guide prophylactic therapy decisions. Early intervention in the second eye often preserves vision much longer than waiting for symptoms to appear.

What is the difference between normal eye pressure fluctuations and glaucoma?

Normal iop in dogs ranges from 15-25 mm Hg with slight daily variations that are usually less than 5 mm Hg. Glaucoma typically involves sustained pressures above 25 mm Hg or significant pressure differences between eyes greater than 10 mm Hg. Single elevated readings should always be confirmed with repeat measurements, as stress or improper technique can cause temporary elevations. Clinical signs such as pain, redness, corneal cloudiness, and vision changes help differentiate true glaucoma from normal fluctuations.

Are there any new treatments for canine glaucoma on the horizon?

Research continues to focus on neuroprotective agents that could preserve retinal ganglion cells even in the presence of elevated pressure. Gene therapy trials are investigating treatments for inherited forms of glaucoma, particularly in breeds with identified genetic mutations. Novel drug delivery systems including sustained-release implants are being developed to improve medication compliance and effectiveness. Stem cell therapy and retinal regeneration remain experimental but promising areas that may offer hope for restoring vision in the future.

Conclusion

Glaucoma in dogs is a complex and potentially devastating eye disease that demands early recognition and proactive management. Understanding the anatomy of the canine eye, particularly the role of the drainage angle and the vulnerability of the optic nerve, is essential for both prevention and treatment. Primary glaucoma develops due to genetic abnormalities that compromise the drainage angle, while secondary glaucoma results from other eye conditions such as lens luxation or intraocular tumors.

Both acute glaucoma and chronic glaucoma can lead to progressive vision loss, with acute cases representing true emergencies that require immediate intervention. Chronic glaucoma, if left unchecked, can result in end stage glaucoma, where pain and blindness are inevitable. Treatment strategies often involve a combination of topical medications—such as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, beta blockers, and prostaglandin analogues—to control eye pressures, as well as surgical options when medical therapy is insufficient.

Regular monitoring of intraocular pressure and close collaboration with a veterinary ophthalmologist are vital for assessing disease progression and adjusting treatment plans. While secondary glaucoma results from identifiable underlying causes, primary glaucoma requires lifelong vigilance and, often, prophylactic treatment of the unaffected eye.

Despite the challenges, many dogs with glaucoma can maintain a good quality of life with early detection, consistent care, and appropriate intervention. By staying informed and working closely with veterinary professionals, owners can help prevent vision loss and manage the complications of this progressive disease, ensuring the best possible outcomes for their canine companions.